Yet, I am learning.

Okay, I know that Michelangelo didn’t really say that. It’s a common misattribution with a traceable origin.

Despite this, I have included it here because it captures an element of life that is very important to me - we can always and should always be learning. Learning can be both forward-facing and retrospective, and in this series of blog posts I intend to focus in on the latter type; reflecting on my experiences and opportunities in the field of data science and what I have learnt from those encounters.

In this first installment, I plan to discuss my summer internship with the global customer data science company, dunnhumby. I will walk through the company and its values, the project I was working on, and the techniques I used to progress. In doing so, I will discuss the challenges that I had to overcome, the problems I failed to get past, and the lessons I learnt in the process.

Background

I will introduce the content of my internship by starting at the top and honing in on my individual work one level at a time.

The Company

If I had to describe dunnhumby in a few words, it would be as the hipster of data science - doing it long before it was cool.

Humble Beginnings

The company was formed by husband and wife team Edwina Dunn and Clive Humby in the late eighties. At that time it was a small operation ran out of the kitchen of their West London home. Despite this grassroots foundation, the company soon developed an impressive client base including Cable & Wireless, BMW, and - most importantly - Tesco.

Even though the specific term was still decades away from entering the mainstream, this work was essentially just data science. Admittedly, the tools and techniques used to solve analytical problems were vastly different - SVMs hadn’t even been invented by this point - yet the motivation, in particular the focus on science and data-led decision making, was the same.

Dunnhumby and Tesco

Dunnhumby originally gained prominence through their work in establishing the Tesco Clubcard. At the time, 1994, Tesco was yet to overtake Sainsburys as the largest UK retailer, and hoped that the creation of a loyalty card could spark this desired growth. Dunnhumby began a series of trials in which they used this new data asset to understand customer shopping behaviour. This was massively successful. The first response from the board came from the current Chairman of Tesco, Lord MacLaurin - “what scares me about this is that you know more about my customers after three months than I know after 30 years”.

From then onwards, dunnhumby has continued to expand into new markets and regions, acquiring many adjacent companies to aid in this growth.

The Chairman’s quote above has been proliferated throughout all sorts of data science literature; two of my favourite non-fiction books - Big Data: Does Size Matter? and Automating Inequality - both include it. Although dunnhumby has kept a generally understated reputation within society at large, it is clear how massive an impact they have had on the world of data science. This prominence and legacy it was led me to apply to a role at the company as soon as it crossed my radar.

Values

Dunnhumby’s work is driven by four overarching values: passion, curiosity, courage, collaboration. I think most will agree that a few of these are quite generic-corporate but the value of courage particularly stood out to me. In my time at the company, I never observed a shyness towards trying new ideas or experimenting. Failure was expected and even relished at times; it was having the courage to give things a go and learn from mistakes that was vital. I think this is an element of their philosophy that makes dunnhumby a good place to work at.

The Team

My original assignment at dunnhumby was to the Security & Operations team. I would have been very happy in this team, developing new security applications with Python. Before I even turned up for my induction though, there had been a change to this plan.

This is due to some much appreciated attention from my original manager who, having had a look through this very blog, realised that I would be far more suited for a research data science role. I cannot express how grateful I am for this level of personal care, especially considering the amount of indifference interns are stereotypically managed with.

This is how I ended up on the HuYu team. Before I get into what the HuYu team is all about, I’d like to walk through the story of its conception.

The Origin of HuYu

Tesco and dunnhumby have a symbiotic business relationship. In fact, Tesco originally bought a 53% stake in 2001 and have since acquired the company in full. Due to this, dunnhumby is given full access to Tesco Clubcard data. This is used to generate insight for Tesco but also to provide customer science solutions to other companies - a key revenue driver for dunnhumby. In 2015 however, Tesco announced that they were seeking a buyer for the company. In the end no sale was made, but if a purchase was successful this may jepardise dunnhumby’s leading revenue source. This got many cogs turning in the company, could dunnhumby develop it’s own in-house data asset to circumvent any future risk that a deal like this could insight?

This is where the HuYu team enters the scene. HuYu is an app developed by dunnhumby which incentivises users to scan their shopping receipts and complete surveys in order to earn points which can be exchanged for shopping vouchers. Any receipts from the eight major UK retailers are accepted including those from home delivery services.

HuYu is designed to be highly multi-faceted, featuring many data sources. In the last few weeks of my internship, the team had just rolled out a trial of a new feature allowing users to link up their search and browse data with the app. There are also long term goals to allow users to share their social media data and general purchase history through their bank in exchange for appropriate awards.

The goal of HuYu is two-fold. The first is to provide a backup data asset in case dunnhumby does one day lose access to clubcard data. But there is also the aim to produce analyses that would not be possible with use solely of one retailer’s data. Examples of such projects are those on cross-shopping or shopper journeys. This also allows further insight into how a customer comes to making a purchase. HuYu’s long-term goal is to capture the whole complexity of this process, from sofa to store.

The HuYu Team

Despite being part of a large, multinational firm, the HuYu team has adopted a distinct start-up vibe. The team is small and budgets are carefully balanced. I was a member of the main part of the team consisting of around five full-time colleagues and a fellow intern. The team also had a handful of members dotted across the globe in Germany and India although the total number of dedicated members was certainly below a dozen. App development was performed by a third-party company with some design and legal assistance from the wider network at dunnhumby.

As a result of this start-up-like environment, everyone in the team was very focused on their own duties and responsibilities. That isn’t to say that there wasn’t any room for collaboration, in fact many of the problems we were facing demanded extensive brain-storming session, but it was the case that no one was ever looking over your shoulder, ensuring that you were indeed completing your assigned duties. This also meant that support was hard to come by; if you had a problem, the first port of call would be extensive independent research and testing. Everyone had their own work to be completing with tight deadlines and so it never seemed fair to bother someone with a problem that you hadn’t thoroughly exhausted yourself. I can understand that this environment would not suit all, but for me this was perfect. I loved the freedom and independence I was given and reveled in the opportunity to solve my own problems and then report back semi-regularity to showcase what I had produced.

The Project

My internship at dunnhumby lasted eight weeks and in the course of this time I was tasked with a project. This revolved around the classification of the receipt items using natural language processing.

The Journey of Receipt Data

When a receipt is scanned using the HuYu app, and after necessary security checks have been made, the image is parsed using Google’s Vision API in order to extract relevant data such as item names and price, as well as transaction level data such as payment method, store location, and shop date/time. The focus of my project was on the item data. On a daily basis, I was working with a large Google BigQuery table containing the name and price of every line item successfully scanned (as well as other meta-data such as retailer name) over the past year or so.

This receipt data is of little use in its raw form; it is very difficult to analyse or make sense of it without any manual filtering or tagging. This is where the classification project comes into play. Before I arrived at dunnhumby, there was an elementary model using the ElasticSearch framework for classifying these scanned line items. The classification challenge was to map each receipt name to a location in an existing three-level hierarchy as well as assigning a brand label if appropriate. For example, an occurrence of the receipt name MCVTS CHOC HOBNOB should be mapped to FOOD CUPBOARD > BISCUITS & CEREAL BARS > BISCUITS with brand MCVITIES.

Improving Classification

As I mentioned above, this existing model was certainly elementary. There were many instances of receipt names that a human could easily identify but the model would fail to do likewise. My main objective during the internship was to either adapt or replace this model to improve the accuracy of classification.

My first week was spent performing extensive research on what machine learning techniques could be applied to this problem. I also have some past experience with natural language processing and so I looked into whether the techniques I had previously used - naïve Bayes, random forests, SVMs - could be applied to this problem. In the end, I reached the conclusion that due to the messiness of the data (the OCR methods were far from perfect) and complexity of the response space, all of these traditional ML methods were inappropriate. I therefore set about finding ways in which I could improve the existing model.

Project Details

Techniques and Approaches

So how did I actually go about improving classification? That is quite a big quite a big question. A open project like this with a goal as broad as ‘improve classification’ can be tackled from many directions, and a lot of the time even indirectly. In this next section I will summarise some of techniques and approaches that I used throughout my internship. It is worth noting though that this is far from a comprehensive list of my work but rather a highlight reel.

Natural Language Processing

The first few weeks of my internship I spent focused on improving the existing ElasticSearch model. This came down to implementing NLP techniques to help the model gain insight into how classification should occur.

Much of this involved ‘teaching’ the model basic rules of English or of the domain-specific language rules that are followed in receipt data. Examples of the generic language rules are pluralisation - understanding that AVOCADO and AVOCADOS are the same thing - white-space handling - SEA BASS and SEABASS have the same meaning - and initialisms - STIR FRY SAUCE can be abbreviated as SFS. There are also some language rules specific to receipt data such as removing vowels from words - humans can easily read WHL MLK as WHOLE MILK - creating edge n-grams - CARAMEL CHOCOLATE BROWNIE can be shortened to CARM CHOC BROWN without loss of meaning - and contractions - replacing STRAWBERRY with S/BERRY. I use the word ‘teaching’ but the processes actually involved creating JSON mapping files which told ElasticSearch how to process the stream of tokens it reads from the scanned receipts and the text in the database it is searching against. I implemented over 10 different NLP techniques in total, many a lot more subtle than those mentioned above.

This gave rise to a modest increase in classification accuracy (evaluated using a moderately sized testing dataset of manually classified receipt line items) but I still felt that I could push things further. A recurring difficultly that the model had at this point was with vague receipt names such as ‘CHICKEN’. As humans, we intuitively understand that this most likely refers to fresh chicken - if it was frozen, it probably would have mentioned. Our model does not have any context for this name though so it cannot use that sort of reasoning. In fact, it ends up favouring frozen chicken. This is a general pattern: when presented with a vague receipt name, the model preferred to put it in a more obscure classification. The reason for this is that in smaller, less bought classifications, there are less unique items and so names don’t need to be as long to distinguish between products. Therefore the search document from an unusual classification has a higher proportion of terms matching a given vague search term and so a match to such classification are favoured. This was a difficult problem to overcome and required a lot of failed attempts.

My initial approach was to try to use ElasticSearch to search against whole categories rather than individual items. This ended up favouring larger classifications where there was more data to match and so decreased overall accuracy. I then tried weighting classifications by their size but this also had a negative impact on accuracy. In the end, the solution I found to be the best was using a two-tiered search system. First, I would complete a search as described above. I would then look at the confidence score that ElasticSearch returned for the top $n$ (whatever $n$ may be best) matches. If either the top score was too low or not distinct enough from the next $n$ results, I would then and only then implement an aggregate search as described above. This was the perfect balance - if ElasticSearch was already confident in its top result then we added no noise or runtime, yet if confidence was low, fallback methods would be employed.

I spent further time throughout my internship on these NLP problems including building custom algorithms for pluralisation handling and vowel removing to deal with some cases that existing algorithms were not suited for (a comical example was COOKED MEAT be identified as GO COOK MEAT TENDERISER because COOKED was stemmed to COOK by the Porter2 stemmer). Overall I managed to improve classification by around 5% in all hierarchy levels. This may sound small, but considering the erratic nature of the OCR algorithms scanning the data and the limitations of the data itself - how do we classify CRISPS at the bottom category level (flavour)? - this was a highly substantial improvement.

HuYu ES Package

In order to improve the ElasticSearch model, I had to go through dozens of iterations each one requiring repeated cycles of tweak, evaluate, and dissect. This was incredibly time-consuming. The existing code that I was using to build models was in the form of a Jupyter notebook with strange dependencies, references to global variables all over the place, and minimal modularity. I felt like there had to be a better approach. I wanted to build models in such a way that my code footprint was as small as possible, evaluation and model explanations were clear, and most importantly edits and new builds could be done as fast as possible.

This motivation led me to develop a Python package specifically for developing ElasticSearch models for HuYu data. The package consisted of a few thousand lines of code with full documentation and examples. This took some time to develop and test but I believe it was worth it. It is now much easier to develop such models and more importantly it is very easy to see individual improvements and regressions when going from one model to another, whereas originally model changes could only be evaluated by overall accuracy. Furthermore, due to a caching feature of the package, it is now much quicker to get predictions from existing models without any changes needed to the calling code. I hope that the package will be used to streamline all future model development. I since I designed it to be as flexible and modular as possible, it can be extended for any new business needs that the team comes across.

Web Scraping

In the last few weeks of my internship I spent some time performing web-scraping using Python (specifically the BeautifulSoup package). This involved trawling through the sitemaps of the Aldi and Sainsburys websites to extract product information (name, description, price, weight, reference code, etc.) from all available items. The purpose of this was to set up the foundations for an eventual re-invention of the classification hierarchy we were using to allow easier matching with non-Tesco products.

To perform this scraping I had to employ a powerful range of regular expressions and assert a tight testing regime to ensure that all data was being scraped correctly (manually verifying the 40,000 links on the Sainsburys sitemap was not an option!). I also implemented multi-processing to speed up scraping, yet managed to do this whilst still utilising progress bars (through the tqdm package) to make scraping user friendly.

Challenges

Unsurprisingly, not everything in my internship went smoothly, and there were many challenges I had to overcome along the way. I will highlight a few here and how I came to overcome them.

Google Cloud Platform

Apart from the development of the HuYu ES package, all of my code was developed in the cloud using the Google Cloud Platform. This is the first time that I have worked with cloud computing although I am now sure it won’t be the last. In many ways this didn’t present much difficulty; my OS of choice is Ubuntu so I am very comfortable in a Linux shell environment. One big difference to my previous experience, however, is the introduction of firewall protections.

On my local system, if I am to spin up an instance of Jupyter, I can simply access it through the relevant port of localhost. This is not the case with cloud computing as the server running Jupyter has a completely different IP address to that of my local machine. This means that port forwarding, SSL certificates, and the likes had to be set up and configured. I learnt a lot about network security in the process and I hope to look into this more in the future. Once these settings were configured very little trouble occurred, yet the initial setup and troubleshooting took up a significant amount of my time.

Standard SQL

A large part of my work revolved around querying the BigQuery database storing receipt data using Google’s own variant of SQL - Standard SQL. My SQL is fairly strong but there were still challenges I faced in using this.

For a start, the Standard SQL dialect is fairly limited when compared to more common choices such as MySQL and PostgreSQL. This makes sense: when working with big data it is much better to have a limited but optimised toolset than a vast array of tools, some of which bring your entire virtual machine to a near halt. This means that I had to rethink the ways in which I would traditionally solve some SQL problems. Without variables, loops, the PIVOT operator, and many other features, I had to spend a fair amount of time researching alternative approaches. In the end, there is no harm in having multiple ways to solve a problem (in fact, there is quite a bit of benefit) and so I am glad to have been forced to adapt to these constraints.

Another discrepancy between BiqQuery and my usual SQL work-flow is the awareness that you are being charged for every query you make. The costs of using the GCP are extremely reasonable, yet I still didn’t want to be wasting money on queries that could be ran more efficiently. This meant considering exactly how I phrased my queries, which joins I was using, and at what point I should create a static sample to work with rather than querying the ever-changing source dataset. The data we were working with was never large enough that subtle inefficiencies would cost us dearly but I’m glad to have had an opportunity to practice this awareness so that I am more prepared if I ever work with truly big data.

The Future

Eight weeks flew by so quickly. I really enjoyed my time working with the team and I would jumped at the opportunity to spend some more time working on my project. Because of the short time I had available, there are many sub-projects that I started but never got a chance to finish. In this section I will talk about some of these and what I believe the next steps are to develop them further.

Regression Models

In week six of my internship, the HuYu team arranged a company-wide day-long hackathon. The goal of this was let the wider company have access to some of the data that we have been collecting and use this to develop to products. Over fifty people attended this event, many dialing in from around the globe via Microsoft Teams, and some great ideas and MVPs came out of it.

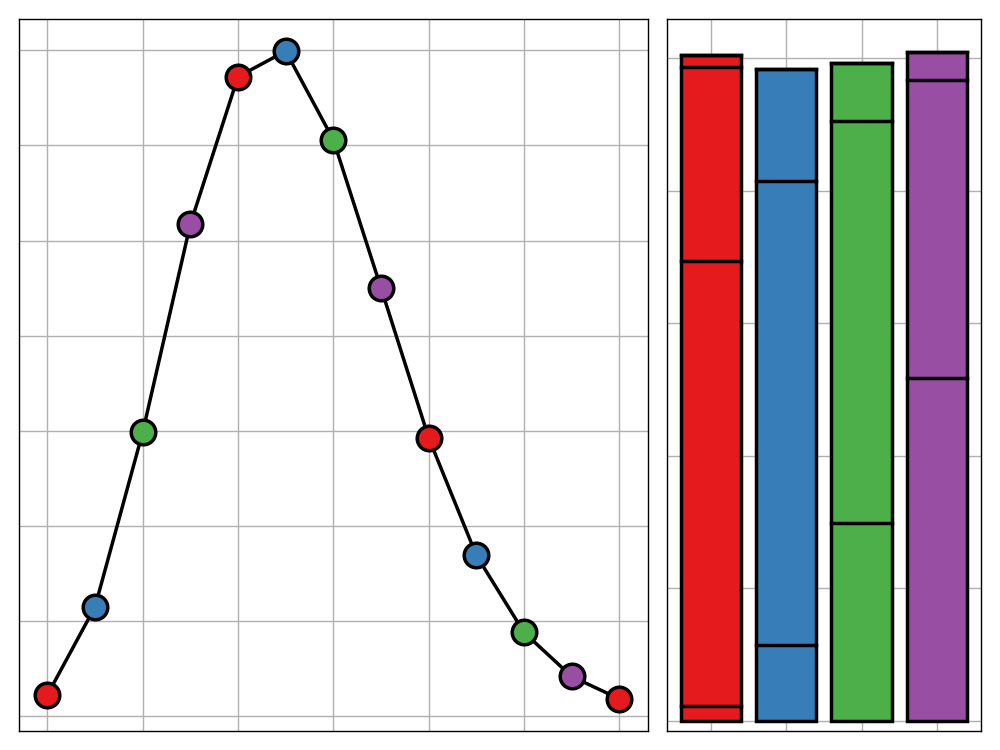

Between the time spent explaining the nuances and limitations of my ElasticSearch model to colleagues, I came up with the idea of using a $L_1$-regularised Poisson regression model to help draw insight from the survey data. The idea behind this would be to take the survey data that we have collected and use the responses as the explanatory variable in a model explaining how many times each user buys a certain product, brand, or category. The previous method of linking survey and purchase data was fairly manual, taking a lot of time and perhaps missing out on insights that an analyst doesn’t test. This is the importance of $L_1$-regularisation in my model: this alters the cost function of the regression model so that any variables with no or low influence on the explanatory variable have their corresponding coefficients brought to zero. This then leaves a selection of survey responses which are discovered to be most influential on a given type of purchase behaviour. This is all processed automatically by an R script I produced. As a MVP I believed that this produced strong results and so would certainly be worthwhile implementing properly in the future.

Tag-based Classification

The current method of hierarchical classification is flawed. It is unreasonable to assume that a given product can only have one classification. For example, a granola bar could be classified in many ways - breakfast-on-the-go, snack, healthy snack, cereal, vegetarian, gluten free. There is also an issue with the existing hierarchy in that it is designed for logistics, not business knowledge. A frozen pizza will be classified as FROZEN FOOD > FROZEN PIZZA & GARLIC BREAD > FROZEN PIZZA but when a receipt just says PIZZA we have no way to even get past the first level of the hierarchy. A classification of READY MEALS > PIZZA > FROZEN PIZZA would be much more appropriate for business needs.

I have completed some preliminary work in extracting tags for products using web-scraping, regular expressions, and some handy product APIs. I hope that these will be implemented once a direction for the classification problem is fully decided upon.

Reflection

With the outcomes of my internship out of the way, it is now a good time to reflect on what I produced and what I can learn from my experience. I will split this evaluation into the things that went well, the things that didn’t go so well, and the things that ended up causing significant hassle.

The Good

Fail-fast, Fail-often

Throughout the internship, I adopted a philosophy of fail-fast, fail-often. Although this mentality is sometimes critisised in certain contexts (particularly, running an entire company according to this is a great way to head towards bankruptcy), I think the approach was very appropriate for my work. For those unfamiliar, the key concept of this philosophy is to try lots of things and not be afraid to through an idea away or put it aside for later study if it is not working. This is almost a literal embodiment of the dunnhumby values - have the passion and curiosity to seek new ideas, yet have the courage to discard them if things aren’t working. This philosophy is important for making sure that you don’t keep going further and further into a tunnel even when it’s become obvious there’s no light at the end.

By adopting this framework in my own work, I was able to quickly test what ideas showed promise and then focus my attention onto developing those further. There were many times where I thought an idea was fruitless, I put it aside and then in a few weeks had a breakthrough that allowed me to push further with it. If I had instead sat hopelessly trying to push the idea before reaching a new perspective on the problem, I could have ended up wasting a lot of time. The key to this approach is to be honest with yourself about you goals and time-frame, and not be afraid to take a step back and evaluate the current intellectual landscape.

Thinking Outside of the Box

When I was first introduced to my project, I was a little bit intimidated. The broad goal of ‘improving classification’ left me feeling like I had no clear direction. It wasn’t long until I started to see the bright side of this scenario though, that because there was no clear path, I was free to invent my own. I spent a lot of time researching: scanning through the ElasticSearch documentation to find new useful features, reading blog posts on similar NLP problems, studying literature about hierarchical classification. I then took the ideas that I had learnt and tried to morph them into new ones that were more suited for the problem that I was facing.

This drive to discover more and then experiment with existing ideas is what led me to implement the top-$n$ fallback method which saw such success in classification accuracy. Other ideas like using Levenshtein edit distance to correct OCR mistakes were also born out of thinking about the bigger picture and trying to step away from what was already implemented. What this process has taught me is that with certain projects it may be beneficial to spend more time in this stage, white-boarding, prototyping, and discovering, to help unearth solutions that I would never have thought of my reaching for the immediately obvious approach.

Minimum Viable Products

One thing that I discovered during my time at dunnhumby is that I have a surprisingly quick turn-around when it comes to developing minimum viable products. Many of the tasks I have discussed in this post - web-scraping, regression models, top-$n$ fallback - went from conception to MVP in less than a day. I then spent time after this refining and refactoring my code but I am proud that I was able to prove utility is such a short amount of time.

This is however a double-edged sword. Developing too quickly can lead to bad code structure which is then a pain to fix in the future. I think the right balance to strike is to spend a short amount of time planning and structuring my code-base before beginning a new task and then engaging in flat-out development with a review period at the end. This format is something I hope to employ in my future work.

The Bad

Pandas is Not Your Friend

I miss R.

Dunnhumby is a very Python-centric company and so to maintain compatibility with my colleagues, the vast majority of my work has been in Python. There are aspects of Python that I really like but the packages pandas and matplotlib are not one of them.

There are a few subtleties of pandas that slowly drove me crazy. The first is the inconsistency with base Python behaviour. Take this for an example.

1 | my_list = [] |

[1, 2, 3]

----------------

Empty DataFrame

Columns: [my_col]

Index: []The logic of both code blocks are exactly the same and yet the output is vastly different. This is because the .append() method for class list acts on the instance of the class directly whereas the equivalent method for class pd.DataFrame creates a copy of the instance, appends to that, and then returns the altered data frame. Since we ran my_df.append(...) in a for loop, this returned data frame is not printed so it is not immediately clear what is even going wrong. I fell for this inconsistency multiple times and there are many other similar instances throughout the package.

Even if I did correct the code to say my_df = my_df.append(...) this still doesn’t work well. Yes, this will run, but it is massively inefficient. This is because pandas will create a new copy of my_df in memory for each iteration of the loop. This is fine when my_df is small, but as soon as it becomes even moderately sized, this will grind your computer to a halt.

Yes, there are alternatives to get round this and similar issues. My point is though that there shouldn’t be so much confusion and inconsistency in the first place. What this has made me realise is that I will need go out and learn more about pandas before I encounter problems rather than as a troubleshooting step since there are many subtle issues with the package that could go unnoticed if not read about before.

Wider Networks

It is evident in hindsight that I did not adequately take advantage of wide range of talent that dunnhumby has in its network. Despite there being facility to do so, I never properly reached out to the company as a whole to see if there was anyone who had relevant expertise to offer me some insight which I could then look into further by myself.

This oversight was epitomised when, in the last week of my internship, I learnt about an interesting unsupervised learning approach which could be used to solve some of the classification issues that I had been unable to tackle. If I had reached out to the company earlier, it is likely that this idea would have reached me earlier too and I may have had time to implement it. Because of by aversion to seek wider support, this idea is now just a footnote in my documentation.

For my future placements and internships, I will make sure that I seek out relevant contacts as soon as possible and then utilise their experience appropriately.

The Ugly

Documentation

Programmers talk about bad documentation so much that it’s almost become a cliché in itself to talk about how we first learnt important documentation is. I have no plan to break from tradition so that is exactly what I plan to discuss.

I left documenting my code until way too late in my internship. This was never going to lead to disaster; my code was fairly neat and easy to follow, and comments were regular. Further, I could remember most of the function of my code and why I decided to write it in the way I did. Despite the final push to document everything was a lot of stress which could have been avoided by regular documentation sessions. On top of that, this could have also improved the quality of my documentation considerably.

Tangential to this is the importance of re-factoring code. I did not assign enough time to this and so when it came to document my code I found myself having to explain decisions that I wouldn’t myself agree with if I still had time to go back and fix them.

This is almost certainly my biggest learning experience from the internship and is something I will take to heart in my upcoming projects and work.

Jupyter Notebooks

This one will be short.

Manually backup your Jupyter notebooks - you cannot trust the auto-saving or even the manually checkpointing. Further, when Jupyter deletes a file, it is likely that it will be gone forever. For that reason be very careful when batch deleting files as accidentally selecting an important file will cost you dearly. As you may guess, I learnt this the hard way.

What’s Next?

On the 2nd September I will be beginning a year-long industrial placement with AstraZeneca, working as a research data scientist. I am raring to go and am excited to implement all of the lessons that I have learnt throughout my time at dunnhumby.

I also have a few personal projects over the next few months. The first is a course of data analysis using the tidyverse which I will be running at a handful of sixth form colleges. Another is a linear algebra Python package that I am developing with a few colleagues from university to practice version-control and Kanban.

You can be expecting a new installment of this series as soon as any of these projects are complete.