Recently, I’ve been working my way through Federick Mosteller’s excellent book Fifty Challenging Problems in Probability. Although the name might be a bit of a misnomer, with few questions proving that demanding for anyone with a decent grasp of undergraduate probability (see Probability and Stochastic Calculus Quant Interview Questions for a more testing problem collection), it’s been a fun read and has provided me with a lot of inspiration for creating my own variants of the showcased problems.

One particular question that I have playing with asks the reader to calculate the probability that a Poisson random variable $X \sim \text{Poisson}\left(\lambda\right)$ is even. The solution follows almost immediately from definitions:

$$

\begin{align}

\mathbb{P}\left(X \text{ is even}\right) &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\frac{\lambda^{2k}e^{-\lambda}}{\left(2k\right)!} \\

&=e^{-\lambda} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\frac{\lambda^{2k}}{\left(2k\right)!} \\

&= e^{-\lambda}\cosh\left(\lambda\right) \\

&= \frac{1}{2}\left(1 + e^{-2\lambda}\right),

\end{align}

$$

where we used the well-known Maclaurin expansion for $\cosh(x)$ to reduce the infinite sum.

Naturally, this led me to think about the generalisation of the problem: what is $\mathbb{P}(X \equiv 0 \bmod d)$ for any $d \in \mathbb{N}$? The rest of this blog post will be dedicated to answering this question, before providing some brief comments about how this result can be extended to any remainder.

However, before we get to that, I would like to take a quick detour to look into the $d=2$ case in a bit more depth.

Tangent: Parity Preference

The result from above tells us that the probability that a Poisson random variable is even is given by $\frac{1}{2}\left(1 + e^{-2\lambda}\right)$. This expression is notable for the fact that it is always strictly greater than $\frac{1}{2}$, meaning that the Poisson distribution has a preference for even numbers regardless of the value of $\lambda$.

I found this to be quite a surprising result and so have spent some time trying to build intuition as to why this is true. The best explanation that I could come up with involves the characterisation of the Poisson distribution as the limit of a binomial distribution with $np_n \to \lambda$ (known as the Law of Rare Events). Using this result, it is sufficient to show that the binomial distribution has a preference for even numbers for $p < \frac{1}{2}$ (for $p > \frac{1}{2}$ the opposite will hold by the symmetry $X \to n - X$).

A nifty way to see this is to label the successes and failures of the underlying Bernoulli trials ($X_i$) as $+1$ and $-1$, respectively. It then follows that,

$$

\begin{align}

1 - 2 \cdot \mathbb{P}\left(\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \text{ is even}\right) &= \mathbb{E}\left(X_1 \cdot \ldots \cdot X_n\right) \\

&= \mathbb{E}\left(X_1\right) \cdot \ldots \cdot \mathbb{E}\left(X_n\right) \quad \text{[independence]} \\

&= (2p - 1)^n

\end{align}

$$

and so,

$$

\mathbb{P}\left(\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \text{ is even}\right) = \frac{1}{2}\left(1 + (1 - 2p)^n\right) > \frac{1}{2}.

$$

Although this is a nice technique, it doesn’t really provide any intuition. For this, the clearest explanation I came up with involved using induction.

Let $P_n$ be the probability that a binomial random variable $X \sim \text{Binomial}\left(n, p\right)$ is even. Then, we have that,

$$

P_{n + 1} = p \cdot (1 - P_n) + (1 - p) \cdot P_n = P_n + p - 2 p P_n.

$$

If our inductive hypothesis is that $P_n > \frac{1}{2}$, then we can write $P_n = \frac{1}{2} + \varepsilon$ for some $\varepsilon > 0$. Likewise, we are working under the assumption that $p < \frac{1}{2}$ so we write $p = \frac{1}{2} - \delta$ for some $\delta > 0$. Substituting these expressions into the above equation, we get,

$$

P_{n + 1} = \frac{1}{2} + \varepsilon \delta > \frac{1}{2},

$$

That is, adding additional Bernoulli trials does not change the parity preference of the binomial distribution. Hence, taking $n$ to infinity, we see that the Poisson distribution has this same preference.

I’m not particularly satisfied with this explanation, nor the need to rely on the Law of Rare Events. If anyone has any better ideas, please get in touch, or better yet, leave a comment at the bottom of this post.

Generalisation to Prime Multiples

Returning to our main task, to calculate $\mathbb{P}(X \equiv 0 \bmod d)$ for integral $d$ we are going to use a clever trick involving complex numbers commonly used in Olympiad-style problem-solving. Specifically, given an infinity series $f(x) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n x^n$, we can write,

$$

\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_{dn} x^{dn} = \frac{1}{p}\sum_{k=0}^{d-1} f\left(\zeta^k x\right),

$$

where $\zeta = e^{2\pi i / d}$ is a primitive $d$ th root of unity. This result is known as the Roots of Unity Filter and an excellent introductory application can be found in Grant Sanderson’s video Olympiad level counting.

For our particular use-case, the identity takes the form

$$

\begin{align}

\mathbb{P}(X \equiv 0 \bmod d) &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\frac{\lambda^{dk}e^{-\lambda}}{\left(dk\right)!} \\

&= \frac{e^{-\lambda}}{d} \sum_{k=0}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right) \\

\end{align}

$$

This result can be verified algebraically, but to gain some intuition, consider expanding each exponential term of the sum as a power series and arranging the results in a table. For example, for $d = 3, \lambda=1$ we have,

$$

\begin{array}{c|ccccccc}

& 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & \ldots \\

\hline

\exp(\zeta^0) & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & \ldots\\

\exp(\zeta^k) & 1 & \zeta & \zeta^2 & 1 & \zeta & \zeta^2 & \ldots \\

\exp(\zeta^{2k}) & 1 & \zeta^2 & \zeta^1 & 1 & \zeta^2 & \zeta^1 & \ldots\\

\end{array}

$$

Recalling that the roots of unity sum to zero, we see that only the columns corresponding to multiples of $d$ have non-zero sums (with value $d$).

From here, all we have to do is perform a bit of algebraic manipulation. For simplicity, I will focus on the case where $d$ is odd, with only a few details needing to be tweaked for the even case. We start by pulling out the $d = 0$ term,

$$

\frac{1}{d} \sum_{k=0}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right) = \frac{1}{d} \left[1 + e^{-\lambda}\sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right)\right],

$$

so we can focus our attention on $\sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right)$. To simplify this term, we write the root of unity in trigonometric form,

$$

\begin{align}

\sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right) &= \sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \left[\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right) + i \sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right]\right) \\

&= \sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) \exp\left(i \sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right).

\end{align}

$$

Noting that the term involving $\sin$ is the polar form of a complex number we can write,

$$

\begin{align}

&\sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) \exp\left(\lambda\sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)i\right) = \\

&\sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) \left[\cos\left(\lambda\sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) + i \sin\left(\lambda\sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right)\right] \\

\end{align}

$$

Finally, by considering the symmetry of the trigonometric functions, we obtain,

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right)

= 2 \cdot \sum_{k=1}^{\frac{d - 1}{2}} \exp\left(\lambda\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) \cos\left(\lambda\sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right).

$$

Note that we are now summing over half the terms, since the other half are complex conjugates. Putting this all together, we have,

$$

\mathbb{P}(X \equiv 0 \bmod d) = \frac{1}{d} \left[1 + 2 e^{-\lambda}\sum_{k=1}^{\frac{d - 1}{2}} \exp\left(\lambda\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) \cos\left(\lambda\sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right)\right].

$$

As far as I can tell, this only has a closed form for the case $d = 3$, in which case we have,

$$

\mathbb{P}(X \equiv 0 \bmod 3) = \frac{1 + 2 e^{-\frac{3\lambda}{2}}\cos\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}\lambda}{2}\right)}{3}.

$$

Either way, we have a reduced a sum over an infinite series to a sum over a finite series, which is much more tractable. If anyone has any clever ideas on how this can be reduced to a closed form, I would be interested to hear—please get in touch or leave a comment.

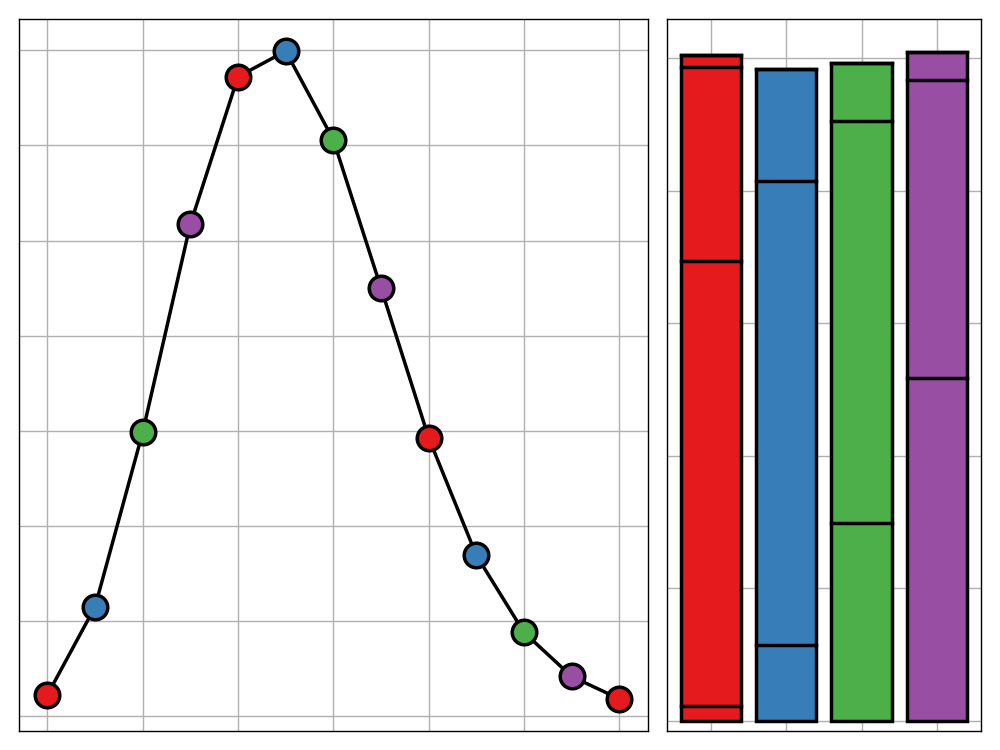

To verify that this is correct, we can compare the results to the Monte Carlo simulation.

1 | import numpy as np |

TEST 1: mu = 2.2, d = 5

Analytic Solution: 0.1584708275917

Monte Carlo Approximation: 0.158391 (±0.00037)

TEST 2: mu = 1.5, d = 3

Analytic Sum Form: 0.35219456292556717

Analytic Closed Form: 0.35219456292556717For even $d$ we simply have to take care over how we treat $\zeta^\frac{d}{2}$ since it has no complex conjugate in the sum to cancel with. I will leave this as an exercise for the reader.

General Remainders

It remains to consider how we can generalise our approach to compute $\mathbb{P}(X \equiv r \bmod d)$ for $r \neq 0$. The change we need to make is fairly simple, so I’ll leave the algebraic details for the reader to verify. The key idea is that by replacing

$$\frac{1}{d} \sum_{k=0}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right) $$

with

$$

\frac{1}{d} \sum_{k=0}^{d - 1} \exp\left(\lambda \zeta^k\right) \zeta^{-rk},

$$

we shift the column of ones in the table above so that it corresponds to the $(md + r)$ th columns for $m\in\mathbb{N}$. Following similar steps to the ones above, we obtain,

$$

\mathbb{P}(X \equiv r \bmod d) = \sum_{k=1}^{\frac{d - 1}{2}} \exp\left(\lambda\cos\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right)\right) \cos\left(\lambda\sin\left(\frac{2\pi k}{d}\right) - \frac{2\pi kr}{d}\right).

$$

Note that as $d \to \infty$ the additional term goes to zero and $X \bmod d \overset d \to \text{Unif}({0, \ldots d-1})$. Again, we can verify this result using Monte Carlo simulation.

1 | def poisson_multiple_odd_remainder(mu, d, r): |

TEST 3: mu = 2.2, d = 5, r = 2

Analytic Solution: 0.2736304014426759

Monte Carlo Approximation: 0.273778 (±0.00045)

TEST 4: Law of Total Probability

Total Probability: 1.0